Published on 12 Sep 2022

Where do we come from? This is one of the humankind oldest questions. Digging in the past of our species is not easy. Further back we go in time, deepest is the darkness that envelops our history. The Upper Palaeolithic rock art of Côa Valley and Siega Verde lights a faint match to understand our history as humans.

According to the fossil evidences, the individuals of Homo sapiens that roamed the Earth 200 000 years ago were undistinguishable from modern humans. At least for what concerns their anatomical features. But even though there was no significant physical evolution in the last 200 000 years of humankind history, a different kind of evolution took place. It is called culture and it is what makes humans…. humans.

Prehistoric tribes of hunter-gatherers didn’t leave any written trace of their culture. Reconstructions and hypothesis about their society and everyday life can be made only through the traces and artefacts our ancestors left behind thousands of years ago. These evidences are of paramount importance to understand who we are, where do we come from and where we are going.

The Oxford dictionary describes art as the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power. The ability of making and appreciating art is one of our species characteristics. And it is deeply rooted in the Homo sapiens ancestry.

For decades, archaeologists recognised only one paradigm for prehistoric art: cave art. This is because the first discovered form of art during the Upper Palaeolithic, between 40 000 and 10 000 years ago, was found in caves from France and Spain, such as Lascaux and Altamira. It seems logic that, in a prehistoric, hostile world, humans sought shelter in caves. In the half-light of these natural refuges, our ancestors gave birth to the earliest forms of art.

However, there is also another paradigm for Upper Palaeolithic art. The lost paradigm described by the Portuguese archaeologist Martinho Baptista as the art of free landscapes. A kind of rock art that is open-air, an artistic experiment testifying the gradually more and more convinced steps our ancestors took in a lost prehistoric world.

Evidences of this lost paradigm were found in the Côa, Douro, Águeda and Siega Verde valleys at the border between Portugal and Spain. 30 000 years ago, after the last big Wurmian glaciation, Côa valley offered a favourable environment to the tribes of hunter-gatherers that were looking for new lands to colonise after the ice retreated. The climate was temperate, and the abundance of flora and fauna guaranteed sustenance for the tribes to thrive.

While roaming the valleys between Portugal and Spain, our ancestors left behind them an astonishing record of engraved rock panels. From a few centimetres small portable plaques up to 2.8 meters engraved schists. 99% of Côa art is engraved, only 1% shows signs of colours.

Nowadays, Côa valley and Siega Verde are part of the UNESCO world heritage list but the way to get there wasn’t easy at all. The rock-art discoveries in Côa started with the construction work of the Pocino Dam to produce hydroelectrical energy. 23 engraved rocks were discovered and studied. At the very beginning, there was no agreement between the experts about the real age of the engravings. They were coherent with the Upper Palaeolithic style in western Europe, however none of the engravings was from a cave and follow the only known paradigm of cave art.

New Upper Palaeolithic paintings and engravings were identified in 1989, when the works for the construction of an even bigger dam begun. The dam was supposed to close the final portion of the Côa river, flooding the whole valley were the palaeolithic art was found.

The archaeological findings were disclosed to the public by the end of 1994. In the same period, the Upper Palaeolithic age of the engravings was confirmed. At that point, the public opinion was split in two. On one side there were people seeking for economy development for a country that was struggling getting out from a rural economy. On the other side there were people asking to preserve the unique treasure of Côa territory. “The engravings can’t swim” said the slogan created by high school students in mid 90s’.

Professor José Riberio, chairman of the Board of the Fôz Côa School launched a school area project to protect the archaeological heritage of the valley. In his vision, schools were places where to grow responsible citizens with critical spirit and not only learning notions. His project with the students had three main points: a series of strictly pedagogical activities, the preservation of Côa cultural heritage and its possible use to attract tourists and foster territorial development.

A campaign was started to collect signatures to stop the dam construction and save the engravings. After three weeks, more than 110 000 signatures were collected. In 1995 the Portuguese government decided to suspend the construction of the dam and one year later, in 1996, the Côa Valley Archaeological park was founded. In 1997 the national rock-art centre was created.

The museum opened to the public in 2010. It was designed by Pedro Tiago Pimental and Camilo Rebelo, from Porto architecture school. The building is located upon a hill facing the mouth of the Côa river and it is designed to emphasize the breath-taking view of the valley. Seen from different angles the museum looks like a schist monolith. Getting closer it is possible to appreciate the complexity of its volumes made of textured concrete, cut by openings with different calibres.

The access to the museum is through a descending opening gradually leading the visitors from the bright landscape to the darkness of the cave room, evoking a primitive period.

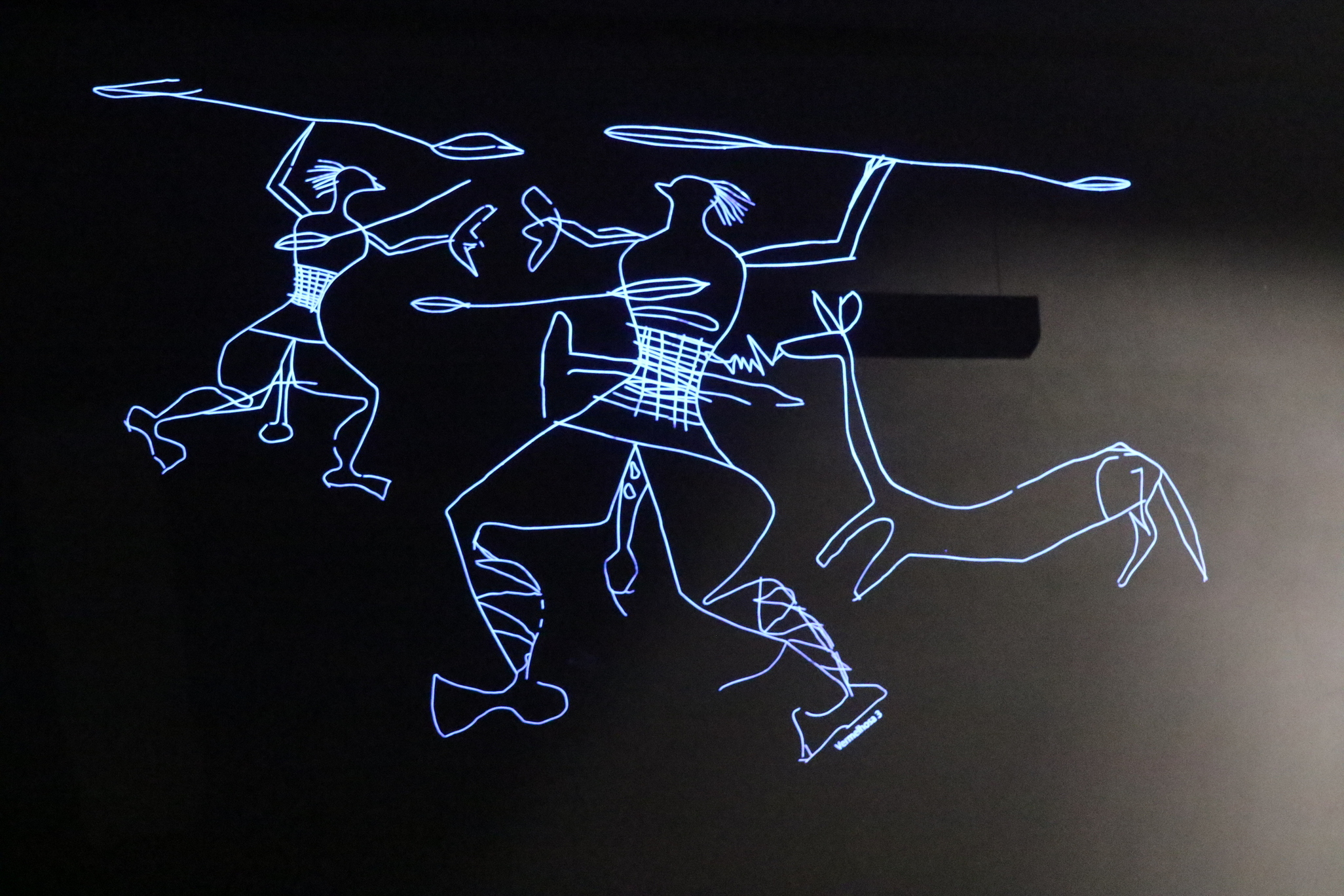

Inside the museum, past and present are wisely mixed to offer an immersive experience to the visitors. Reconstructions of the rock-art, soil and rock samples, and pictures of the archaeological park are displayed in the museum’s rooms, side by side with interactive panels and augmented reality screens.

The museum also has a place to host exhibitions of modern artists inspired by prehistoric art in their works. This link between past and present, ancestors and descendants, is part of the richness of Côa Valley heritage. A treasure preserved by the former generations for the younger ones, as said by the Archaeological Park and Museum guide Dina Regalo in her interview.

Despite the strong demographic recession of the last 50 years, several preservation and cultural initiatives blossomed in the Côa territory. The cooperation between public and private stakeholders fostered the development of new opportunities in the territory.

Taking part in European projects such as TExTOUR not only helps designing a sustainable model for cultural tourism in the territory of Côa Valley, but also creates an international network of cultural heritage sites and a series of shared good practices.

Cultural tourism activities are a way to preserve the unique archaeological heritage of Côa Valley while developing a business system that helps young people to settle in the region. It is important that young people believe in the project of the museum and archaeological park and in the future development of the Côa Valley and Siega Verde territory.